The Soviet people considered Latvia to be the best example of “socialism”. What they didn’t understand is that when the Soviets took over in 1940 , all they did was take over the structures from Capitalism that already worked well. These weren’t the byproduct of the USSR, but leftovers of the independent country of Latvia. This was in stark contrast to the rest of the Soviet Union where the Communists destroyed all remnants of the tsar post 1917.

The Soviet people considered Latvia to be the best example of “socialism”. What they didn’t understand is that when the Soviets took over in 1940 , all they did was take over the structures from Capitalism that already worked well. These weren’t the byproduct of the USSR, but leftovers of the independent country of Latvia. This was in stark contrast to the rest of the Soviet Union where the Communists destroyed all remnants of the tsar post 1917.

The generation born post 1945 grew up knowing about “the old country”. Their parents would call the streets by their old names and tell the stories of the capitalistic freedoms and what it meant to live in the open vibrant cosmopolitan European city that Riga was before soviet occupation also described as “Paris of the East” by its visitors.

Somewhere in the background of all these stories was the mysterious lure of America as the beacon of freedom – surpassing all other countries of the world, including those in Western Europe. Even though most people had never travelled there, most families had a relative who pre the Soviet era had visited there as a tourist or a worker, or moved there after the war. The culmination of all these stories was an intense fascination with “America as the best”. In the late 50-s and early 60-s “American way of life” with iconic figures like Elvis, James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, president Kennedy and high living standards was dominant in Europe and naturally had a great influence on Riga’s youth. That was the basis of the Shtatnik philosophy. Shtatniki were the children born post-Soviet occupation who grew up with stories about America. Some children of Russian occupants who grew up with the Latvian children and their stories also joined the Shtatnik movement (1940 Latvia was 77% Latvian, 10% Russian, 13% -others; post-1945 Latvia was 62% Latvian, 33% Russian, 5% -others). These Russian children were especially impressionable since they had not been around any “American” products or positive information before. These occupants were also generally poor families who were resettled in Latvia to water down and “sovietize” the Latvian “Western” population. They had grown up with Soviet propaganda (that Russia is the best) and were completely brainwashed that America was a wasteland for the proletariat.

The first prototype of the Shtatniks was the STILYAGI (“Hipsters”). Stilyagi emerged in the 1950s in Riga. This generation was born in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Since Riga was a port city, there was more access to foreign sailors who would bring records and provide examples of clothing and hairstyle (through how they looked). The Stilyagi blackmarket flourished on contraband music (copies of swing/jazz/early rock records), copying the pompadours and fashions (skinny ties, wide shoulder jackets, narrow pants). The Styilagi movement was apolitical – it was strictly about copying music and clothes. It became political only because these cultural influences were prohibited and people would be harassed by police, employers and teacher for the simple fact of how they looked and behaved. By the end of the 1950s, many STILYAGI had grown up – started to get married, had to blend into society to be able to support their new families, and they gave up this movement. The movement began to wind down.

In the early 1960s, Jack and a few of his friends who were in their early teenage years saw that they had missed their chance to be Stilyagi and wanted to start their own movement: about building their own little America inside of Soviet Riga. The movement started absolutely apolitical as well and was influenced by the parcels many people would receive from their relatives abroad as well as the contraband they would smuggle from the sailors (magazines, newspapers, records, clothing, chewing gum, etc.). By the mid 1960s, there were about 100 jeans-clad teenagers with crew cuts, button downs and chewing gum. Their role models included James Dean, Elvis Presley, Cliff Richards, Chuck Berry, Chubby Checker, Bill Hayley, etc. Music was still the main driving force – as it is for most youth movements around the world. The only difference is that they had absolutely no access to Western music in the USSR – unless it was smuggled. Western radio was completely blocked by govt. sponsored sound interference (which cost the USSR a lot of money). Once in a while on a long wave radio there might be a few seconds of a Western program of music or commentary (Voice of America, BBC) that Shtatniki and often their parents would eagerly listen to from the privacy of their home. If someone was to report you as listening to this program – you would be severely reprimanded at your place of work.

In the early 1960s, Jack and a few of his friends who were in their early teenage years saw that they had missed their chance to be Stilyagi and wanted to start their own movement: about building their own little America inside of Soviet Riga. The movement started absolutely apolitical as well and was influenced by the parcels many people would receive from their relatives abroad as well as the contraband they would smuggle from the sailors (magazines, newspapers, records, clothing, chewing gum, etc.). By the mid 1960s, there were about 100 jeans-clad teenagers with crew cuts, button downs and chewing gum. Their role models included James Dean, Elvis Presley, Cliff Richards, Chuck Berry, Chubby Checker, Bill Hayley, etc. Music was still the main driving force – as it is for most youth movements around the world. The only difference is that they had absolutely no access to Western music in the USSR – unless it was smuggled. Western radio was completely blocked by govt. sponsored sound interference (which cost the USSR a lot of money). Once in a while on a long wave radio there might be a few seconds of a Western program of music or commentary (Voice of America, BBC) that Shtatniki and often their parents would eagerly listen to from the privacy of their home. If someone was to report you as listening to this program – you would be severely reprimanded at your place of work.

As for parents of Shtatniki – they tried to curb their childrens’ desire to copy American styles since it was punishable and dangerous for the whole family in terms of career, school, etc. Deep inside though, the parents (just like their children) knew that their destiny was in the West – in America – one day.

In the 1960s, cinema was the main source of recreation for Latvians. The USSR had mandatory political newsreels that preceded any feature film. Most of these were anti-American propaganda reels that showed line-ups of unemployed, garbage heaps, urban decay, the decadence of Broadway and the pinnacle was Elvis Presley swinging his hips. This strategy backfired: the Shtatniki would go and occupy the first three rows of the theater just to see these “negative” few seconds of Broadway lights or Elvis’ hips and loudly leave right after these few seconds appeared on screen (to the scornful glare of the Communist and military people in the audience).

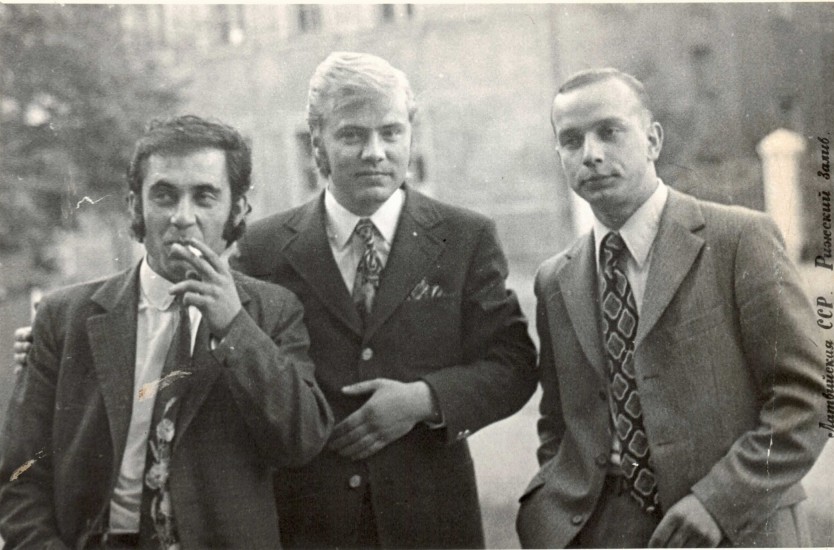

Shtatniki were obsessed with learning any small piece of information about America. The movement grew to be several hundred people. Buying and selling foreign clothes exploded on the Black Market and locals would try to reproduce some of these foreign fashions (imitation blue jeans stitched out of dark fabric). The Shtatniki movement even developed even their own fashion lexicon! “McNamaras” referred to reflective sunglasses (like the ones Robert McNamara wore in the 1960s) , “Playboys” meant desert sand boots (which they’d seen in Playboy), etc. All of this was underground.

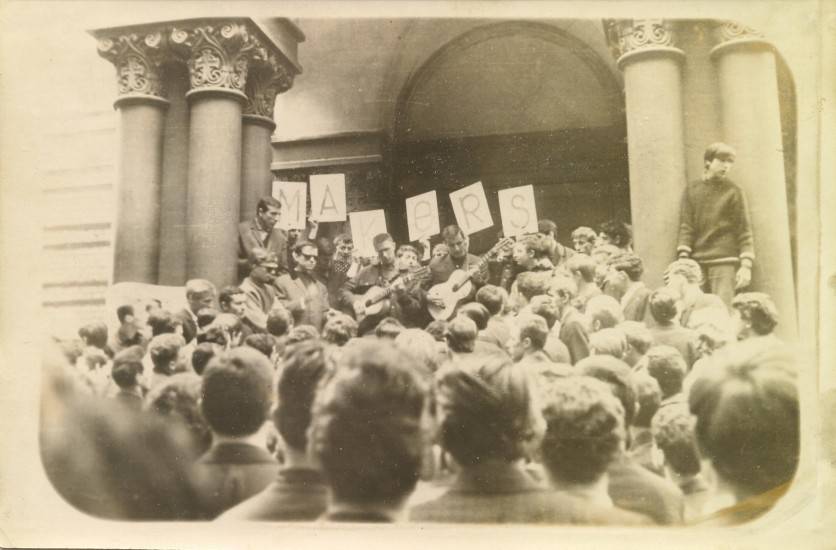

Musicians started behaving more boldly – publicly singing the songs of The Beatles, Tom Jones, Engelbert Humperdink, Beach Boys, etc. They would often be arrested or publicly humiliated (broken guitar, cut hair, slashed clothes). The first non-violent demonstration in the Soviet Union was in April 1966 when the concert of the local Western-imitating band (the “Melody Makers”) was cancelled by the authorities. It was scheduled to take place in the “Planetarium” (former Church that the Soviets transformed over night by sawing off all the crosses). All the tickets were already sold out in advance and nobody wanted to return their tickets. The Melody Makers decided to play acoustically right there on the stairs of the concert hall in spite of the KGB agents that had arrived to watch and film everything that happened. An enormous crowd of fans stood for more than six hours outside the building, right in the center of Riga, carrying banners saying” “FREEDOM TO GUITAR!”, “MAKERS” and other anti–authorities slogans. Passers-by joined in the demonstration, while the militia stood by bewildered until nightfall finally dispersed the crowd.

Musicians started behaving more boldly – publicly singing the songs of The Beatles, Tom Jones, Engelbert Humperdink, Beach Boys, etc. They would often be arrested or publicly humiliated (broken guitar, cut hair, slashed clothes). The first non-violent demonstration in the Soviet Union was in April 1966 when the concert of the local Western-imitating band (the “Melody Makers”) was cancelled by the authorities. It was scheduled to take place in the “Planetarium” (former Church that the Soviets transformed over night by sawing off all the crosses). All the tickets were already sold out in advance and nobody wanted to return their tickets. The Melody Makers decided to play acoustically right there on the stairs of the concert hall in spite of the KGB agents that had arrived to watch and film everything that happened. An enormous crowd of fans stood for more than six hours outside the building, right in the center of Riga, carrying banners saying” “FREEDOM TO GUITAR!”, “MAKERS” and other anti–authorities slogans. Passers-by joined in the demonstration, while the militia stood by bewildered until nightfall finally dispersed the crowd.

From this moment on, the Shtatniki gained a lot of momentum with more and more people taking part. It was a non-national movement (Russians and Latvians were on equal ground), but the uniting belief was that the only place to be where freedom means freedom is the United States of America. The only way to get to America during those days was by an invitation from a relative (which still didn’t guarantee Soviet approval). If approval was granted, you had to leave all your possessions, pay for all your previous schooling (and all the other “state-expenses”) and renounce your citizenship. Very few people managed to leave in the mid to late 1960s. The first official immigration wave was triggered by Nixon’s visit in 1972. He asked for the USSR to honor the international rule of “family reunification”. This became the way that the Shtatniki could leave…

From this moment on, the Shtatniki gained a lot of momentum with more and more people taking part. It was a non-national movement (Russians and Latvians were on equal ground), but the uniting belief was that the only place to be where freedom means freedom is the United States of America. The only way to get to America during those days was by an invitation from a relative (which still didn’t guarantee Soviet approval). If approval was granted, you had to leave all your possessions, pay for all your previous schooling (and all the other “state-expenses”) and renounce your citizenship. Very few people managed to leave in the mid to late 1960s. The first official immigration wave was triggered by Nixon’s visit in 1972. He asked for the USSR to honor the international rule of “family reunification”. This became the way that the Shtatniki could leave…